The Defenseman Compass

My attempt to categorize defensemen

A few weeks ago I wrote something called the “Microstat Player Compass” for forwards & promised a defenseman version of it in the future. It seemed like an easy enough idea on paper & some of the same concepts apply. You have your elite players like Cale Makar who are great at everything, a tier that is just below them of players who fall in the 10-35 range in any random order & others who are complementary players with different skillsets. This is where things get dicey.

It’s easier to parse out some of those skills for forwards because outside the top & bottom tier players, defensemen’s results can be more influenced by their surrounding environment. It sounds counter-intuitive. They play more minutes, get more puck-touches and can “control” the game more than forwards and while that’s true for the upper-echelon players, you have a lot more who sit in the middle of the pack. These players are usually at the mercy of what the forwards in front of them do or reacting to whatever the game situation is.

A good puck retrieval in the defensive zone only means so much if the next guy makes the right play, the same can be said for a controlled exit having the same impact as clearing the puck out if the forwards can’t make a play in the neutral zone. Microstats help bridge this gap to a degree, but team influence has more of a role here than it does with forwards. That’s why a lot of defensemen see their numbers bounce around from year-to-year, especially when switching teams or coaching staffs & it also applies to microstats, especially on the extreme ends.

You have a team like Buffalo that played a firewagon style of hockey last year. Most of their defensemen were below the league average in Zone Entry Defense stats, namely their big-minute players.

The flipside is the Los Angeles Kings, who love to stack up their own blue line & their defensemen’s stats bear that out.

Player tendencies are also a factor here, as entry denials is the most repeatable stat of zone entry defense, but the rate to which chances & controlled entries are allowed is more prone to team-effects. Players on the extreme ends are usually safe, but the middle of the pack is where you can get some misleading results.

The same can be said for zone exits, although more for teams on the extreme ends of the spectrum.

Take Carolina:

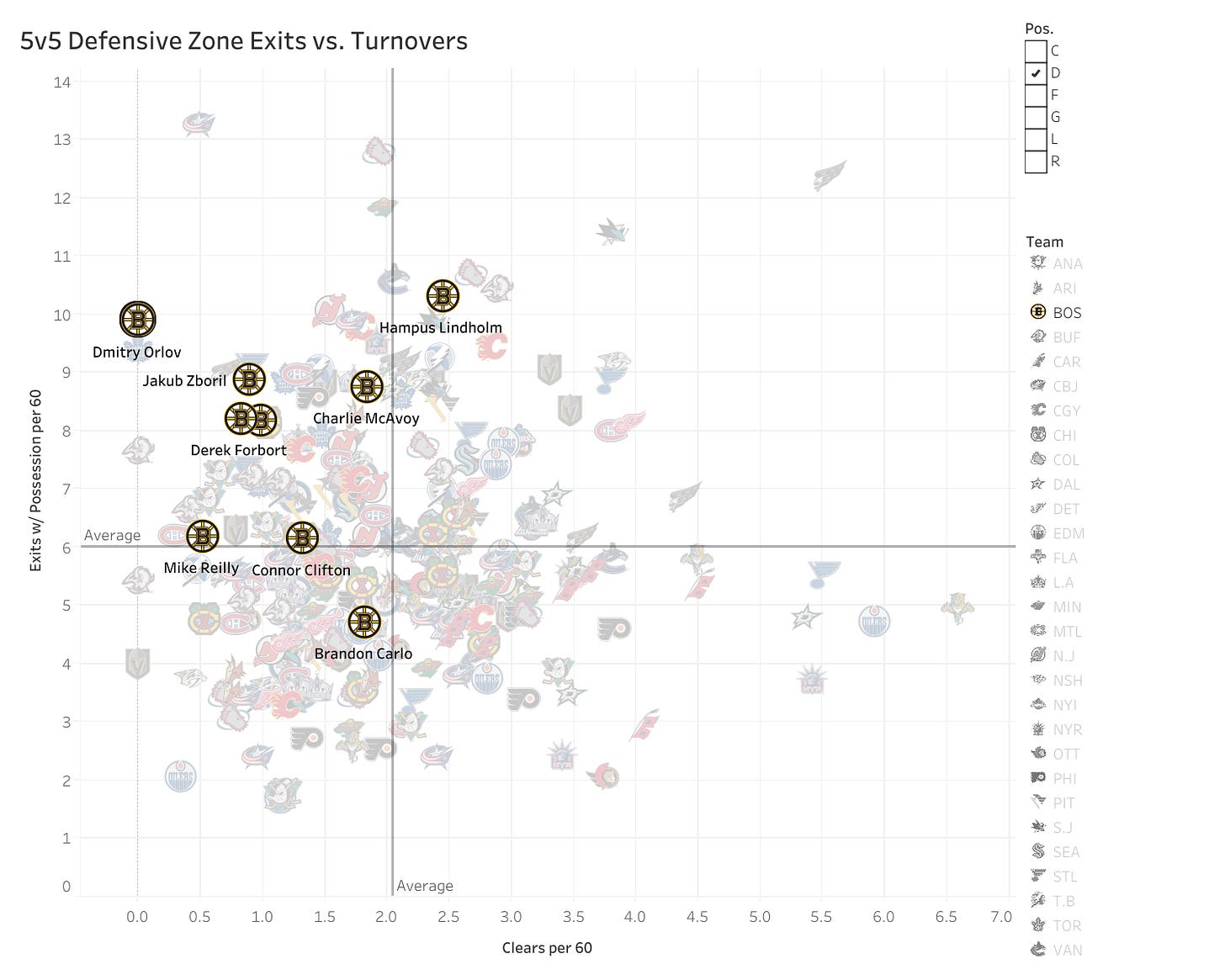

and then Boston:

One team tries to get the puck out by any means, while the other looks for more controlled plays. Both succeeded in the regular season, but you can see why it can get tough to compare these stats across teams. There are players who will not see their numbers change despite whatever chaos is going on around them, the defensemen just a tier below the elites who excel in the details of the game (see Chris Tanev, Jared Spurgeon, Mackenzie Weegar), it’s just a matter of finding those through all the noise.

This is why the whole player compass method with defensemen was more of a rubix cube. There are A LOT of stats to breakdown, some of them more explanatory than predictive. They tell you what happened & how the player performed, but it doesn’t necessarily mean the player is good or bad at a certain skill.

So, which stats should we start with and what should we focus on?

Sorting Out The Noise

Impact is one thing, but so is consistency. Turnovers in front of the net affect the outcome of the game, but how often does the same player do it? It’s not as often as you think, which is why we’re looking for repeatable skill.

A starting point is looking at controlled zone entries, because we know that’s a repeatable stat. I expanded it a little by including carried zone exits to create a player type called “Rushers.” The reason I’m including carried exits is that it’s the most repeatable of the exit types for a defenseman & the most that comes down to individual skill, as you have to be able to skate & move through a forecheck to be good at this. Some outside factors play a role (i.e. puck retrievals), but the defenseman retrieving the puck isn’t always the one exiting the zone, so this is where we can start to categorize players.

Here’s a quick glimpse at some of the players in the Rusher category:

This is where you parse out the defensemen who have some level of puck skill or explosiveness, the high-end being Erik Karlsson & Roman Josi. Maybe not everybody’s idea of the perfect defensemen, but game-breakers who are going to be Norris front-runners as long as their legs still work. Then there’s the next tier of guys like Quinn Hughes, Chabot and Dahlin who were drafted high because of their gifted skillsets. You also have some of your trusty stalwarts like Pietrangelo, Hedman, Makar and Lindholm hanging around the top side of the graph along with maybe some surprising names to some who don’t get to watch every team (Jensen, Dobson, Walman).

The nice thing about this stat is that players usually show this skill early & sustain it. Jake Walman is probably the latest example of this. He was a good puck-rushing defenseman in St. Louis that couldn’t find his place in the lineup & didn’t put up much offense despite frequently joining or leading the rush. He was traded to Detroit where he eventually got more minutes & was a top-pair defenseman for them last season. What’s interesting is that he’s a different player now that he’s higher in the lineup, not leading as many rushes, but some of the skills translated over to the other parts of the game, mainly with setting up offense and leading zone exits off retrievals.

Goes to show that some defensemen can thrive in one area & use it to adapt to other parts of their game once they get more minutes/responsibility. It’s tough to project how they’ll do because it usually comes down to getting the reps in, but a young defender excelling in one area is usually a good sign that they can carve out a role at the NHL level. Vince Dunn is another example of that, as he broke out as a top-pair guy in Seattle last year after years of excelling as a puck-mover in lower roles.

The lower end of this is the player Walman was traded for in Detroit, Nick Leddy. I’ve talked about him ad nauseam because he’s an excellent skating & puck-moving defenseman who topped out as someone who just eats a lot of minutes while not providing much offense or ice-tilting ability despite this skill. He has been the same player his entire career & you know what you’ll get from him, which is a placeholder who gives your blue line some mobility but not the greatest results. Can you do better? Absolutely, but if that’s the worst case scenario, it’s a good place to start.

You also have a couple young players that haven’t quite found their way yet. We don’t know much about Jamie Drysdale yet because his second year was cut short by injury. Adam Boqvist was a frequent healthy scratch in Columbus & has one of the more broken defenseman profiles I’ve seen.

There could be something with him because the offensive talent is obvious. He is also the most extreme player I’ve tracked from a “great at rushing the puck, terrible at zone exits” standpoint, the latter being the more important skill if you’re a defenseman and the one coaches focus on the most. The best-case scenario for someone like him is Brandon Montour, who has a similar profile but isn’t nearly as chaotic with exiting the zone. Worst case scenario would be Brad Hunt, who is still hanging around as a utility defenseman.

Now that we’ve covered this, let’s move onto the actual compass.

The Defenseman Compass

I’m going to be brief with the other categories because there was a lot I wanted to cover with the Rushers category & it’s more “system-proof” than the other categories. These stats highlight which players excel in the details of the game while the rush & offense components show you what makes some players standout on their own.

Similar to what we did with the forwards, we’re going to use the individual components of microstat game score in an attempt to categorize these defensemen. It’s a little different from the last post because we’re going to place the players on more of a grid rather than using rigid quadrants. The stats I’m using for this are Zone Entry Defense Game Score, Carried Entries/Exits per 60 and Zone Exit Game Score. I mentioned that systems have an effect on these stats, but one way we can work around it is by placing more weight on some of the more repeatable skills:

Carried exits

Possession Exit%

Entry Denial per 60

Chances allowed off Controlled Entries per 60

Successful DZ Retrieval%

This is so we don’t have players on the same team in one quadrant. I only started tracking puck retrievals in 2021-22, so we have a two year-sample to work with and the stats listed above had the most stability when players switched teams or coaching staffs. Defensive zone puck retrievals are also baked into Exit Game Score & more emphasis is placed on the percentage of successful retrievals as opposed to how many they have per game. More emphasis is also placed on chances on controlled entries against as opposed to all entries as a way to isolate one-on-one defending situations and entry denials to measure a player’s tendency instead of their results.

Basically, we want to make this as cross-compatible as possible & we’re left with a chart like this at the end of the day:

From then, we can start to place players into different categories while keeping the rush component from earlier in mind. The top right is the “two-way” quadrant where most of the top defensemen in league are, your strong play-driving types who typically post great underlying metrics every year. There are some lower-lineup players hanging around like Carson Soucy, who turned a nice season with the Kraken into a three-year contract with Vancouver where he’ll likely play a bigger role.

The lower right quadrant are the more high-risk puck movers. They give you a lot of offense while also giving a lot back. These are what I call the Rorscach Test defenders because everybody sees these high-risk players differently. Some only focus on their mistakes while others will hype up their strengths as puck-movers & offensive players. There’s also a couple of tough-minute defensemen here like Filip Hronek & Ivan Provorov who handle a lot of defensive zone usage on bad teams.

Also in this quadrant is Erik Karlsson & Roman Josi, which goes back to how these are never going to be everyone’s favorite defensemen, but the most dynamic, game-breaking types are in this group. Most here fall into the “Rusher” category discussed earlier.

The top left players are “stoppers,” or the one-way defensive types whose main strength is defending entries or shutting down plays at the blue line. The playing style of these types is a little different than it was 10-15 years ago, because everybody can skate now, so they have some mobility & offensive upside. The league average is just higher now, so players like this are stuck in more utility or penalty killing roles, as there are more guys in the top-four who can move the puck & deny entries.

We’re not going to focus too much on players in the bottom-left, but most of them fall into the “stopper” category, just in defensive zone play rather than neutral zone defense. Either they’re strong in-zone defender or better away from the puck.

After all that boring stuff, let’s move onto the fun part:

The Actual Compass:

This isn’t a rigid study by any means, but the four categories show what I was going for here. The players on the right are your stronger puck movers that are easier to replace, but have some boom-or-bust nature associated with them. Sometimes on a shift-by-shift basis. The players are the left are more malleable to what the team’s system is and have their strengths away from the puck. Probably mroe reliable in the eyes of the coaching staff & will see their number jump around more compared to the players on the right.

I also tried putting the players with the most outlier-ish stats on the edges of the chart just as a baseline. Josi, for example, is on the bottom right because he’s the most extreme puck-rusher in the league and not because he’s bad at entry defense. Cale Makar has the best all-around stats when it comes to zone exits & denying entries, so he owns the top right. Jaccob Slavin has one of the highest entry denial rates in the league & one of the lowest Possession Exit% along with it, so he’s in the top left. Ristolainen retrieves a lot of pucks and….doesn’t really do anything else with it, so bottom-left it is. Basically, the most extreme examples are on the edges & everyone else builds out the quadrant based on what their strengths lean towards rather than how “good” or “bad” they are at a certain stat. Hence why I placed Noah Hanifin in the dead center of the chart.

From then, I tried to build out the chart with as many defensemen as I could think of using the guidelines from the A3Z data. It’s not perfect, but it gives a slightly different look of what I try to do with this project rather than just throw a bunch of stats at you. Where you can start to have fun with it is building out a lineup, like last year’s Vegas' squad.

I moved a few guys around since there’s more room on the chart. Vegas is one of those teams that has a more minimalistic appraoch with what they look for in their blue line. Pietrangelo & Martinez handle top-pair duties with one guy being the puck-mover & the other being a puck-eater. Similar dynamic with Theodore & McNabb except McNabb is a little more physical with how he defends & Theodore is more of a free-wheeler than Pietrangelo. Then you have Zach Whitecloud on the bottom-pair, who is a great puck-mover that doesn’t put up a lot of points & is great at denying entries. His partner, Nic Hague, is usually the first guy on pucks and plays a more simple game.

Aside from Pietrangelo, they don’t have an all-around guy (and even his entry defense stats are dicey) but they have six guys who complement eachothers skillset well, which goes back to what I discussed at the beginning of the article. There’s other team examples I can point to, but we’re already 2k words in so I’m going to call it for now.

Conclusions

Creating defensemen archetypes is difficult because players can change their habits under different coaches & different systems. However, there are some skills that are repeatable and you can create a baseline from there.

Puck skills are something usually developed early & it can be the difference in a defenseman becoming elite. Not neccessary to be a good player, but it’s easier to build out your lineup when you have these guys.

More work can be done to find ideal defense pair types, but it can be subjective & something I want to dive into in the future.

Analyzing defensemen is hard.

Hey, this is really interesting. As an Ottawa fan it was interesting to see where Chabot excelled, especially as he is becoming something of a whipping boy here. When he makes a mistake, it’s often very visible because he is trying to make a skilled play. Newt to see Sanderson show up too. We love him in Ottawa due to his smooth skating and great positioning and are excited to see if his puck skills will shine through in the next few years ans he transitions from retrieval, to exits to zone entires.

Also, paragraph near the bottom indicates that Risto is “bottom right”, but should have said “bottom left”.

Thanks for this!

Really great stuff. I would be curious to see some more analysis on team-movers and the effect on play style. Might be a project for me given all the data you provide...