Information Overload

Embracing the grey area in hockey analysis

Sometime ago, I made the decision to be a hockey analyst. My niche was watching games through a different lens, gathering stats that aren’t tracked by the league and using those to form my own analysis. It leads to some interesting discussions. Most of the time it’s just another way to hype up players you already know are good, but there’s always a few interesting finds. You see why certain teams might overachieve (The Blues & their passing) or why others aren’t scoring as much as they “should” (Carolina’s love for point shots). You also learn the subtle ways in which some players are good & appreciate some of the middle-of-the-roster guys that you might gloss over when watching the game casually. It’s not something I expected everyone to be into, but there was always an audience & a desire for more information.

The cool thing about sports statistics is that you don’t necessarily have to be a math person to apply them. If your definitions are clear or relatable to what happens during a game, it’s easy to weave them into your analysis to supplement your opinions. This was the foundation of All Three Zones, back when I was doing rudimentary stuff like scoring chance & zone entry tracking. It was another layer to help me as an analyst & it led to some interesting discussions about why certain players are struggling or why coaches deployed players a certain way.

As the project grew, I added more data with hopes that I could create an “all-in-one” look at a player’s skillset or how a team’s system works. A couple hours into building my first player cards, I realized that this is a tougher task than I thought. It’s rare for players in the NHL to be terrible in every measurable category now, especially with enforcers being a thing of the past. Most guys have a niche or a role that they fill even if they don’t have the prettiest statistical profile. Likewise, you’ll have some objectively good players with underwhelming microstats because most of their contributions come away from the puck. It makes for a good starting point in analysis & what I can do to make my own dataset better. At the same time, I can’t spend 5 hours to track one game to account for literally every event so there has to be some sort of trade-off.

There aren’t too many issues with forwards. It’s fairly easy to gauge the high-skilled guys from the ones who are there to forecheck and kill penalties. Every once and awhile you’ll have someone like Joel Eriksson Ek or Paul Stastny who excel despite never touching the puck, but the results are straightforward for the most part. Defensemen, on the other hand, are a bit of a riddle. This isn’t meant to overcomplicate things, but there are a lot of factors that go into judging defensemen. They play more minutes, have more puck touches and go through stretches of games where their job is to let nothing happen. Breakouts and zone exits are one way, but flipping the puck out of the zone to relieve pressure can be just as impactful as a clean zone exit depending on the situation. This isn’t even getting into how exiting the zone usually takes a couple of passes and the one-man breakouts don’t happen as often as you think. Trying to nail down everything into just a few statistical categories is almost impossible.

At the same time, I don’t want to get into the habit of tracking stats for the sake of having data available. Things like pass blocks, stick checks or some type of “shots negated” metric might be cool to have, but it also runs the risk of creating noise & churning out player cards that are longer than Chris Jericho’s List. It might have its purpose but the issue becomes whether or not it’s worth manually tracking, adding an extra 20-30 minutes of workload onto a plate that’s already full & cutting into the sample of microstats we already have (shot assists, zone entries, entry defense).

It goes back to why I switched my zone entry tracking to charting puck retrievals in the defensive zone rather than exits. The player exiting the zone isn’t always the one making a play under pressure or starting the play, where a successful retrieval usually involves getting the puck away from a forehecker to create a numbers advantage elsewhere. If they aren’t, it’s to get the puck out of harms way, which also has its place. It happens often enough in a game that you can measure whether or not it’s a repeatable skill. Retrievals are also where most plays begin, whether it’s to create offense or to prevent a chance, someone has to go back to get the puck and make the first play. From there, you can start to get a sense of where rush offense starts and where plays can go wrong in the defensive zone.

Nailing it down to an individual stat is the tough part, because retrieving the puck is only the first step and not every play has a 1 or 0 value depending on the situation. There are times where you have to take a hit & just throw the puck to an area where nobody is instead of making a low-percentage pass. You also might have a good retrieval turn into a nothing play or a turnover because the play fell apart at the second level. This is where microstats turn into more of a gauge of playing styles rather than something that tells you if a player is good or bad. This also has its purpose because, as an analyst, it helps me explain a player’s on-ice results or why he might be a bad fit for a certain system. A defenseman who is an adept passer might have his skills go to waste on a team that doesn’t have any forward talent to supplement him and a forward might have trouble creating anything off the rush if his defensemen can’t retrieve the puck without turning it over.

It's a double-edged sword for me because it takes awhile for me to gather the data & I’m usually moving onto the next game before even diving into the bones of what happened in the last one. The data often leaves you with more questions instead of the easy answers some might be hoping for & that’s part of the fun of being an analyst, even if it might not be the best for posting quick player profiles whenever a trade happens. It kind of forces you do dive into what happens during the doldrums of the game & appreciate the subtle qualities of the game’s elite players.

Drew Doughty’s most recent season is a good example of this.

Doughty is a top-pair defenseman on a playoff team. He also plays more minutes than almost anyone else in the league. His profile is more scattered than you’d think, but one area where he excelled last year was puck retrievals. He had a large workload here and was very efficient when it came to getting the puck out of the zone off those retrievals. Turnovers were mixed in, but the puck usually got out of the zone if Doughty was the one going back to get it. Looking at some of those plays shows why it’s an important part of the Kings game & why he’s posted such good results despite not being the coast-to-coast player he used to be.

There’s a couple of things to notice. First is how swiftly Doughty moves the puck once he gets it. It’s quick and effortless in nature. He takes one look over his shoulder and immediately knows what his next move is before he even touches the puck. It makes for some efficient breakouts, but also requires good plays from the forwards for it to materialize into anything. Sometimes Doughty will lead the rush, but the Kings forwards do so much of the legwork here. Doughty makes their job easier by getting it by the forechecker, which is part of why the Kings were such a good transition team last year. It also shows why their offense might have struggled. One of your most explosive players is stuck behind the play and the forwards already have to burn some energy getting through neutral. It’s also putting a lot of trust in your forwards to be in the right spot & make the correct read because the puck is moved Add in the fact that they’re defending a shift & it’s easy to see why Doughty’ posted some good on-ice results despite not having much direct offense. There’s only so much he can do, but being strong on retrievals helps make the job for the rest of the Kings easier. We saw some of this dynamic last year too with Mattias Ekholm & Roman Josi.

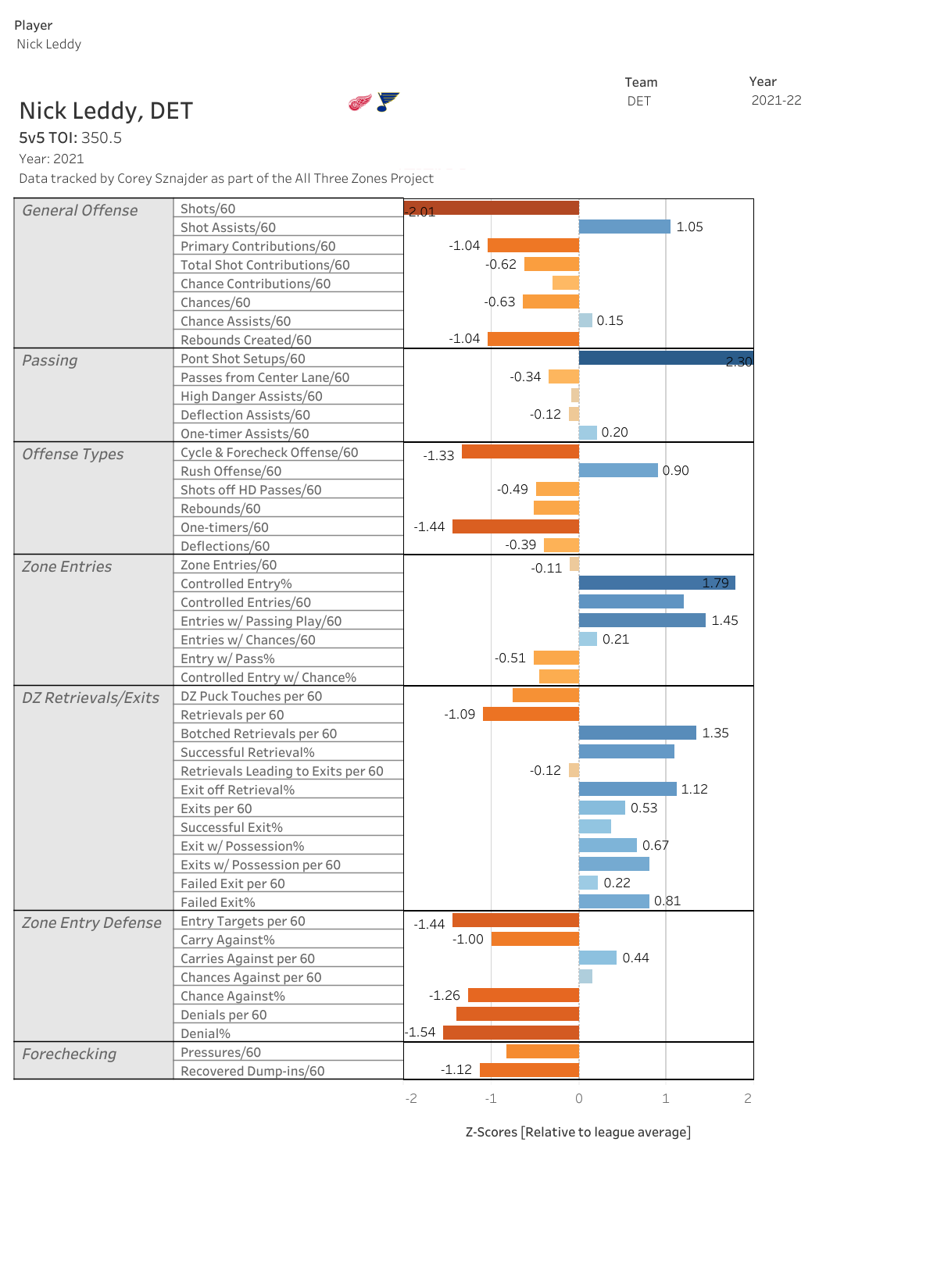

Sometimes you have the opposite case, the best example being long-tenured Islander Nick Leddy.

Nick Leddy has been the same player for his entire career. A fluid skater who can be a one-man breakout, make some nice plays in transition but take a beating when it comes to on-ice stats. You can see why in some of the stats. Most of his offense comes off the rush (which are usually one-and-done opportunities) and he rarely shoots the puck, so his profile is very limited despite his talent. He’s also one of those rare defensemen who is good at exiting the zone but not retrieving the puck. Showing that he needs help from his partner or his teammates to use his skillset, also some insight into why his on-ice numbers have been so poor for most of his career. The other thing to remember about Leddy is that he was a top-four defenseman while the Islanders were having their best year and is expected to play the same role for the St. Louis Blues.

His skill with the puck is something teams value despite his warts. I’ve always wondered if there’s a risk-reward trade-off that teams are hoping to get with him. You have a guy that is going to eat a lot of minutes and it’s not always going to be pretty. He will have to survive some defensive breakdowns and take a beating on the shot/scoring chance ledger, but you’re hoping that the goaltender can bail you out enough for Leddy to give you a nice rush out of the zone to flip possession. I think back to the playoff game against Colorado where he got posturized by Nathan MacKinnon and still made a key play with keeping the puck in to help the Blues win the game in overtime. Getting off the mat & not letting mistakes affect your game isn’t necessarily a quantifiable skill, but I do wonder if it’s something coaches look for when evaluating players. It’s like a pitcher who walks a few batters or gives up a couple of early runs but ultimately keeps their team in the game after six innings by shutting the door for the rest of the game. Leddy sort of reminds me of that with how he goes about his business.

Is it the most efficient way to play? Probably not. The best defensemen in the league average maybe 2-3 entries a game, so you’re relying on rare events that other teams gameplan for & most of Leddy’s breakouts aren’t logged as retrievals or exits because they come off reloads where you have to go through stationary neutral zone defense rather than forechecking pressure. That said, coaches still value him because he can do something like this once or twice a game and hockey is decided so often by the margins. The question is whether or not those few splash plays are worth the trade-off you get with the rest of his game.

Another player who is valued by coaches is noted analytics punching bag Rasmus Ristolainen. This is more of a recent one because I try not to pile on players most fans have a negative opinion of. Risto’s an interesting case, though. He spent most of his career on bad Sabres teams and was getting the Duncan Keith/Brent Burns treatment in terms of ice-time. Then the trade to Philly happened and Ristolainen stayed in the top-four but played more of a high-minute second pair role instead. His results didn’t change (poor on-ice numbers where the Flyers were outscored & outchanced while he was on the ice) but the team opted to re-sign him to the standard five-year, $5+ mil. contract every team gives their middle-pair defensemen.

With microstats, you’ll find most players in the NHL have some sort of skill and Ristolainen is no different. However, it’s a little more complicated than just a single bar chart can explain.

Ristolainen grades unfavorably in most stats, which isn’t a surprise because most of his game is based on what he does without the puck. However, the notable exception is retrievals. Some people from Flyers Twitter have brought this up to me and there’s a few conclusions. Charlie O’Connor, who has watched more Flyers hockey than any human ever should, summed it up nicely in his review of Ristolainen’s season. Pointing out that his microstat profile shows some of his strengths. Risto is very good at playing along the boards, going to get the puck and causing a scrum. He has some strengths in the offensive zone that end up being more window-dressing because he spends so much time defending.

You can get a sense of why coaches like him. He’s big, plays a physical game and is usually involved in the play in some form. The downside is that his puck skills under pressure are among the worst in the league, same goes for defending zone entries. So at the end of the day, you have a defenseman who can break up some plays in the defensive zone, but the puck usually doesn’t go anywhere unless a teammate is helping him. The Flyers recognized this by pairing him with Travis Sanheim, one of their better puck movers, and the two were one of the Flyers better defense pairs last year (at least compared to the rest of the team). Ristolainen himself didn’t have great numbers, but he had some chemistry with Sanheim and some of the game tape shows why having a puck-mover with him is so important.

Handling the puck doesn’t come easy for Ristolainen, he takes a second to settle it down, which invites pressure and while he eventually cleared it out of the zone, it took a few attempts to make it happen. There’s a lot of this with Risto’s breakouts. Maybe there’s something to be said about having a partner who will do the simple things to free up space for the more talented puck-movers but it’s a tough way to go, especially if you’re not playing with the lead much. Also seems curious to pay someone as much money as the Flyers are giving Ristolainen to play this role when you can call almost anyone up from the minors to do the basics, but maybe this is where teams value his physical tools more than we do as fans? It’s hard to say because Risto has been the prime example of a player that fans & hockey front offices have been divided on for years. Microstats, particularly puck retrievals, show some of what we might be missing, but the rest of his profile raises more questions than answers.

These are just three examples, and you can get a sense of how many directions you can go with microstat analysis. When I started this project, I wanted to build a tool that would be a go-to for player analysis. I knew that would be complicated and lead to some pitfalls because that’s what happens when you try to present a mountain of new information. Sometimes you get over-excited to show everyone how much work you did and overwhelm your audience instead of taking it slow with integrating it into your work. The trap I usually fall into is going to lengths to show how meaningful the data is instead of using it to illustrate a point that everyone can follow.

It goes back to why I started doing this type of analysis in the first place. Microstats were a helpful tool for me as a blogger because they were based on practical events that were easy to notice while I was watching the games. Passing, zone entries & zone exits are what stood out to me and as I got deeper into this type of work, I started to really dig into the bones of the game & create some pretty cool stats out of them. Are they a magic tool that tells you if a player is good or bad? No. Are they still helpful for me when looking into the why of a player’s results? Absolutely. Like all analysis, there is going to be some grey area, moreso in hockey, but that’s part of the fun with covering this sport.