With the season upon us, I figure now is a good time to take stock of some of the All Three Zones data. If you haven’t been following, I added some new stats to the package last year, looking at the “context” behind rush offense or where the rush starts from. Both in terms of which zone originates & the situation where it was created. Basically it’s an effort to link entries, exits & shots together.

The main reason I added this is to add some practical aspect to my own analysis. As a coach, it’s easy to say you need to create more rush offense but what’s the best way to go about it over the course of the game?0 Are you trying to force turnovers to poach for counter-attacks, be patient & regroup in the neutral zone or put a few passes together out of your own zone to generate an attack with support? This is something I was hoping to quantify & I took my first crack with my presentation at the Seattle Hockey Analytics Conference in 2022.

I tracked every goal from the 2021-22 season, which zone the play started in and more specifically, how the rush was created. Every team wants to create off the rush or “win the battle in the neutral zone,” but how do you go about doing it? Some teams are methodical, letting their best puck-handlers cook and regrouping if they can’t find any open lanes to enter the zone cleanly. Others let the play come to them, relying on counter-attacks or forcing turnovers in the neutral zone to get a fastbreak type of look the other way.

Carrying the puck in is also viewed as less of a high-risk play than it used to be. Turning the puck over in was a cardinal sin & something only the best players on the team were given the green light to do not that long ago. Now, almost every team has someone on all four lines who can carry the puck & it’s not always an offensive play.

Rush play has increased, which also means it has become a more mundane part of the game. Just as the forwards have gotten better at excelling in the transition game, defenders and teams have adapted with shutting it down. Even if they concede an entry, defensemen today are very good at maintaining a gap & limiting forwards to one-and-done looks. Some players have the ability to break through that structure, but it’s not a frequent occurrence & the higher percentage chances don’t happen until the game breaks down.

Take a rush like this.

and one like this.

One is against a set defense from a controlled situation & the other is off a counter-attack where you have the defenders out of position. I already had a method of separating these types of plays out by noting if a scoring chance occurred off the entry, but it’s a little crude and not always black-and-white. Scoring chances aren’t created equal, especially off the rush and a sequence like this would get marked as an entry leading to a chance even though it didn’t directly happen off the rush.

I’ll touch on this specific topic later, but adding context to the entry was my main goal last season & I wanted to go over some of the preliminary results compared to what I found in my 2021-22 project. I didn’t get as many games tracked as I wanted, so I can’t get into the team-level results yet, but I did find some interesting results league-wide.

You can read my Seattle presentation or my post on it here full explanation of my tracking process but the cliff notes version is I tracked which zone each play originated from (offensive, neutral, defensive) and whether the play started off a neutral zone turnover, neutral zone regroup, a neutral zone re-load, a controlled breakout (against no forecheck), a defensive zone exit/retrieval or a counter-attack/offensive zone turnover. There is some grey area & subjectivity with this, but I tried to stay as rigid as possible with my definitions, although it was tough game-to-game. The biggest thing I was looking for was how effective slow, regrouping types of plays were compared to playing more of a north-south game or simply playing on the forecheck.

In my Seattle project, I found that 47.8% of five-on-five goals occurred off the rush and 65% of rush goals originated in the defensive zone. The biggest proportion of defensive zone rush goals came from counter-attacks (41%) and defensive zone exits (35.5%), whereas 51% of goals originating in the neutral zone came off turnovers with a very small percentage occurring off regroups & reload plays.

In other words, turnovers and clean breakouts are the key to rush offense and anything you get from other areas is a bonus. This was just looking at goals, though. This year I wanted to expand it and look at all shots to see if certain rush sequences lead to higher percentage shots compared to others. Defensive zone exits & retrievals were the most common type of rush goal, but which one had the most risk & reward?

2023-24 Season Results

My tracking process was the same as the Seattle process, except I tracked all shots that weren’t blocked. The table below shows the shooting percentage for each rush situation out of shots on goal, how often a shot got on goal, the frequency of each rush situation & the rate per 60 minutes.

Some of the results from the Seattle project line up here. Most rush shots start in the defensive zone, with a big chunk of them starting from a clean exit or retrieval with counter-attacks being the big feast-or-famine category. Counter-attacks were marked separate from retrievals if the exiting team didn’t have to beat a forecheck or forced a turnover high in the zone to start a rush, whereas a retrieval is an exit where they had to beat forecheck pressure. Controlled breakouts were the lowest occurring type of rush but shots off these plays found the back of the net at a slightly higher rate compared to exits against a forecheck. In other words, they were good plays but the toughest to accomplish.

As for neutral zone play, turnovers reigned supreme here & they occurred at only a slightly lower rate than reload or regrouping sequences. They also didn’t occur at a high rate relatively speaking, so it’s a small piece of the pie overall. This kind of goes back to my thought of carrying the puck not being as risky of a play as it used to be. You risk giving up a higher percentage shot if you do turn the puck over, but players are so skilled now that it doesn’t happen that often in the context of a game.

What is interesting is that other offense that starts from the neutral zone is very average in terms of finishing. Reloading (or quickly re-entering the zone) and regrouping are fairly common tactics with a few teams but they aren’t getting much of a reward from it. This isn’t black-and-white because the play doesn’t always end with one shot off the rush & some teams like to start their forecheck or cycle off a controlled entry instead of dumping the puck in, but it was just interesting to see how these were the two categories that dragged down the overall shooting percentage for rush offense.

The cliff notes version of this would be:

Most rushes start in the defensive zone with a clean exit.

Clean defensive zone exits against a forecheck are the most repeatable way to create rush offense, but forcing turnovers in both neutral zones create higher-percentage shots. Why some teams who can counter-attack ride a wave of shooting percentage over the course of the season.

Neutral zone offense is a small piece of the puzzle, but a rewarding one if you’re good at forcing turnovers.

With this, you can link some of the A3Z data together to get a clean picture. Applying this to a coaching or a practical standpoint is the next step. It’s tough because the game is unpredictable and counters/turnovers are where you let the play come to you whereas reloading, controlled exits & regrouping are more of a conscious decision & you can control that part of the game slighltly more.

That said, there could be something here you might be able to identify with a larger sample. Take a player like Kyle Connor for instance. He led the league in counter-attack goals in the 2021-22 season and is notoriously a great shooter but an awful defensive player. You need to spend time in your own zone to get counter-attack chances, so there’s a feast-or-famine element to his game. How many goals do you lose if you tell him to play more conservatively in the defensive zone or try to reduce his usage there? If you’re looking to acquire him in a trade, do you see his counter-attacking strengths as something that can help your team or a flaw that you have to work around? The counter-striking ability is great, but it takes up maybe 10-15% of the game compared to the other 85% that he might struggle in. Although, if you’re a team pressing for offense, it’s a risk you might take because goals are still at a premium and he is a guy that can help.

If you’re a team like Carolina, who likes to dump the puck out and start their rushes going downhill in the neutral zone, or do you try to create more rushes from your own zone (keeping in mind that over 52% of all 5v5 goals still come off the forecheck)? Do you stick with that as your main offense and rely on the higher-percentage turnovers for your rush offense? Florida employed a similar strategy last year with dumping the puck in almost 60% of their entries, but were around the league average in rush shots created instead of near the bottom. Having balance is usually what this comes back to, but having the players & system to achieve that can be done in different ways.

I would imagine if you’re a team getting one-and-done looks off the rush you would encourage your guys to wait & start a cycle with more support because there’s more of an opportunity for sustained offense. Whereas if you’re deploying a scoring line with great shooters who aren’t good at forechecking, you might tell them to force something off the rush because it’s their one chance at offense. This is where the shots off retrievals come into play even if you’re not scoring a lot of goals off them. It’s the most reliable way of playing off the rush & that can help you with dictacting the terms in the the territorial game.

The game situation also plays a role here because you’re not going to force controlled exits when defending a lead in the third period or if you’re getting forechecked to death, but this is also where utilzing the A3Z data can help. Some players are good at finding routes out of the zone as the second guy & some defensemen are great at taking hits to start exits to help beat an aggressive forecheck. Same with finding players who can enter the zone against a set defensive structure without needing to poach for turnovers.

The Other Half

The other part of the project I wanted to touch on is in-zone offense. I don’t want to say I’ve neglected this, but the foundation here has been set for awhile. It’s based on Ryan Stimson’s guidelines from the passing project where you track the lane of the pass and if it was a low-to-high play to the point, a royal road pass or a pass from behind the goal line. Nothing has changed here much. Shots directly off low-to-high plays only go in about 3% of the time while passes from behind the net lead to a Shooting% of 14.7%. The frequency of low-to-high plays was double of behind the net plays despite this, though.

This is where I wanted to look at the passing sequences a little more in-depth bebcause I don’t think teams are purposefly creating lousy low-percentage shots on purpose. The point shot is never meant to be the end of the sequence, but more of an attempt to get the defense scrambling so you can recover & maybe create soemthing else. There is also always the hope that you might get a deflection or a rebound, which is why I wanted to look at passing sequences where a low-to-high play was involved rather than the final play.

Things change quite a bit. The shooting percentage goes up if a low-to-high play is the second to last pass, although 41 of those 65 goals were deflections or tips. Which are 50-50 plays in my tracking because they miss the net almost 50% of the time. Although an interesting note is that 27 of them started from a low-to-high pass from the right side of the offensive zone. Not sure if it it means anything with a sample size that low, but it was odd to see it so heavily skewed towards one side. Deflections made up a little over half of tertiary low-to-high assists, but again, we’re dealing with a low sample size here. Also backs up the general studies of more passes yielding better shots.

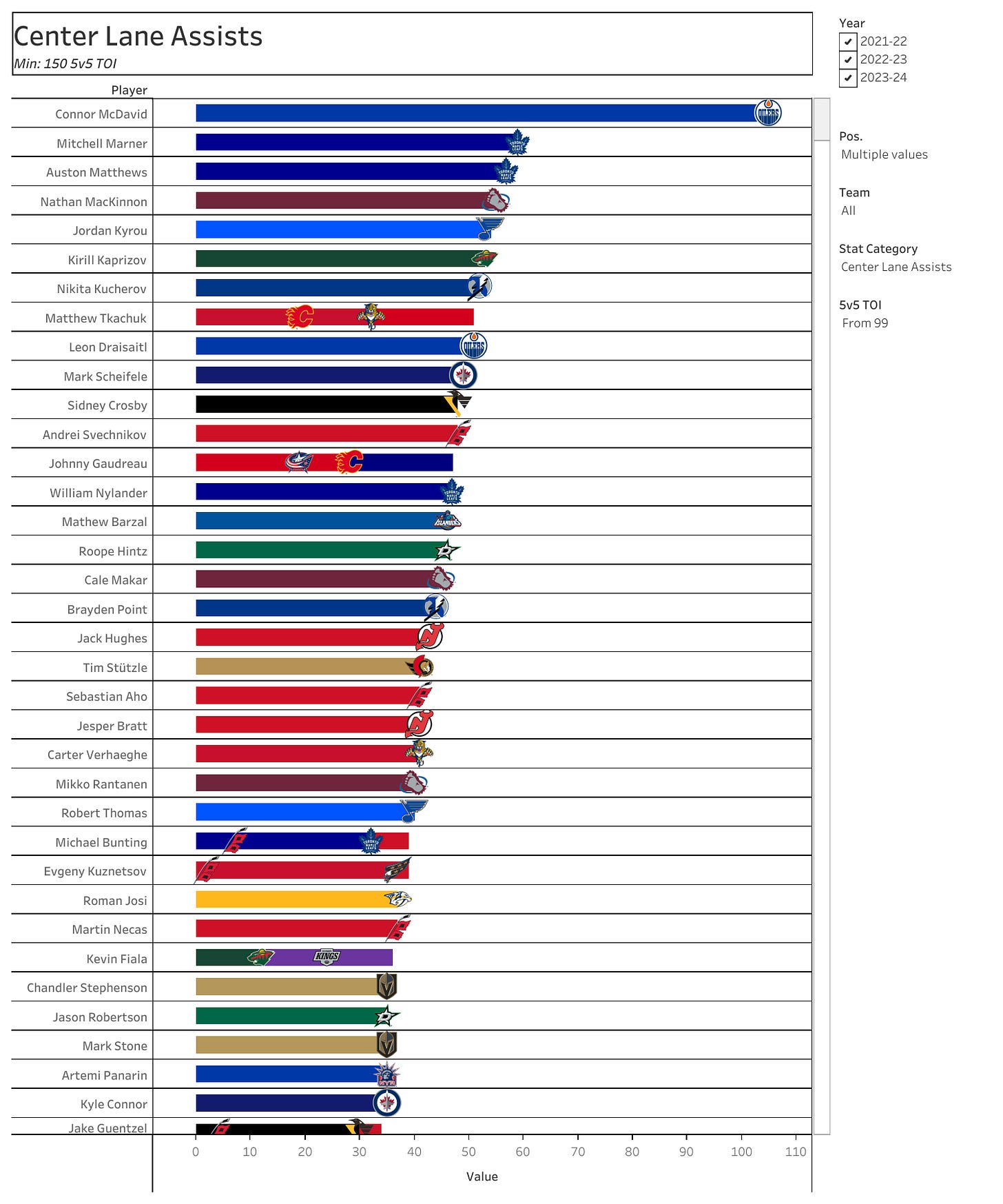

The one consistent thing I’ve found with in-zone offense is passes from the middle are the most optimal & repeatable method for creating better shots. The shooting percentage on those was 11.8% last season & has stayed above 10% for my entire eight-year sample. This is regardless of the pass type or how far away from the net the play is. You see teams cycle high in the zone all the time now & I would assume that’s an adjustment from how defenses key-in on taking away passes from behind the net now. I always want to find a better way to quantify those, but the leaderboard for players who create passes from the middle usually passes the smell test well enough.

I always want to get more into the weeds & track more specific things with cycle & forecheck play (especially from a defensive standpoint), but sometimes I forget that what we have now is pretty good at finding a signal.

2024-25 Goals

First priority is obviously getting a bigger sample size so we can dig deeper into the player & team level stats instead of just league-wide data. I have thankfully broken out of the ESPN+ prison this year so I have the means to track these games in a more efficient matter this year. I also want to do a better job of not grouping all rush offense together with all offense that happens off controlled entries. Mostly because I think there’s something to the carry vs. dump-in debate with roster construction & setting up your offense off a controlled entry instead of having to constantly play on the forecheck. I like keeping everything the same for continutity sake, but I also want to have more fine-tuned data, obviously.

I also want to open the forum to the subscribers for what they want to see more of & will be getting started on that soon with three subscribers to the Bedard Tier already (you’re in luck if you’re a Hawks, Stars or Kraken fan). More system analysis is something people always ask for more of & while I’m not that in-tune with coaching tactics, the data here does a pretty good job of catching what teams like to do & I can always build something off that with some game footage added in. Hoping the articles I’ll do as part of the Bedard Tier allow me to be a little more interactive & introspective with the project this year instead of going through the motions with tracking games & getting the data out.

Aside from that, I’m pretty happy with where the project is going and I’m excited to get going with the season (which starts today!).

Hell yea. I’m gonna go listen to some Karp I’m so pumped. Keep up the diligent work my dude!